|

μια σελίδα αφιερωμένη στο "φτωχό θέατρο" του Jerzy Grotowski ...

με υλικό που θα εμπλουτίζεται συνεχώς με νέες αναρτήσεις ... μια επιλογή από σκέψεις, άρθρα, μελέτες και άλλο υλικό ... |

a page dedicated to the "poor theater" of Jerzy Grotowski ...

with material that will be regularly updated with new posts ... a selection of thoughts, articles, studies and other material ... |

Student Assistant to Jerzy Grotowski Reveals Secrets

From Inside the Lab

When the Polish theatre guru came to teach in Irvine in the 1980s, he turned the group into a new experiment in mystery and discipline.

BY KEITH FOWLER

In the mid-1960s, grainy pictures and reports reached us from Poland that there were some remarkable dramatic rituals taking place in Wrocław with a group calling itself the Polish Lab Theater. The director was a young man named Jerzy Grotowski, and he identified the style of his work as “poor theatre.”

I was teaching at Williams College, and I was eager to import Grotowski’s visual effects along with whatever I could imagine of his theatrical ideas. I taught a class on Antonin Artaud at the time, and was interested in the “double,” the ineffable presence (like some invisible dragon) that Grotowski’s rites seemed to conjure. I was mounting a production of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine that I ended up directing with what I took to be Grotowski-inspired notions of poor theatre. I was fascinated by the roughness of expression, a crude authenticity that owed nothing to refinement. I admired not only the raw texture, but what I could sense of Grotowski’s point of view. Back then I craved a tangible message—not a dogma, but a credo to guide an audience with intelligence. Troupes that lacked a statement struck me as flabby and weak. Grotowski asserted a vision, but I fear I missed it. I doubt my Tamburlaine had more than a superficial resemblance to the Lab Theater.

Some 15 years later, in 1983, Grotowski joined our department at University of California–Irvine. The details of his arrival included his use of a renovated barn south of our campus. He also required a yurt, a solid-wall version of a Mongolian tent. These structures have become quasi-sacred edifices since his death.

I was pleased that one of my MFA directing students, James Slowiak, was chosen to work with Grotowski’s initial group. A bright and curious artist, Jim swiftly earned Jerzy’s trust, becoming his personal assistant for many years. As for the faculty, after an initial meeting, we had no regular contact with “Groto,” the students’ affectionate name for him. As the academic year got under way, I felt left out. I told our chair I wanted to join in. Weeks later, I received a nighttime phone call; an unknown male voice told me to come to an address in Laguna Beach the next evening. “Wait,” I said, as he was about to hang up, “What is this address?”

“It’s where Jerzy is staying.” Click.

Laguna Beach is a touristy seaside city, an artists’ colony and beach volleyball Mecca of fewer than 25,000 people, 20 miles south of Irvine. It was not where I had pictured Grotowski.

The next night I arrived at the address and rang the bell. Jerzy appeared, with a cigarette in his hand, wearing a dark sweater with a darker sport coat over it, his shoulder-length hair damp and uncombed. He said softly, “We go to the café, yes?” He nodded vigorously toward the corner and started in that direction. He led us silently toward the White House, a popular tavern. He aimed for the back—to a section quieter than the traffic in front.

I asked the waiter for a beer. Jerzy ordered a meal, and we began to talk. I learned that the Work, “Objective Drama,” involved exposing performers to Haitian shamanic traditions. Students would be instructed in song and dance by practi-tioners of Afro-Haitian-Catholic hybrids of Santeria andVodou. And, as I would learn in our group’s dryly joking fashion, our masters were witch doctors. The aim seemed to be to discover what, if any, effect such age-old rituals might have on us. Whether thisparticipation effect might be a revival of old skills or an impact on our ideas of self, I never knew.

THERE WAS MUCH I NEVER KNEW. Years later, hearing from others what Jerzy was doing, I realized how his legacy could be, in Richard Schechner’s words, so “well known and obscure simultaneously.” Lisa Wolford’s research pinpoints his elusiveness and changeability. Given that he shared little information directly with his subjects, we confabulated explanations for his protocols and exercises. It is fair to say that all who worked with him had a unique experience.

The White House jukebox played “Hotel California.” As Jerzy came to the end of his meal, I asked how he was enjoying California. He nodded quickly. “I like it here,” he said, “with young people who are so beautiful, healthy and smart.” The waiter brought the bill. I reached for my wallet, but Jerzy was already prepared. “Please,” he said, and handed his credit card to the waiter. Whenever I think back on that evening, I smile to think of Jerzy Grotowski treating me in a California saloon with his American Express Gold.

He never said that I was admitted to the group, but I was later informed of the starting date. To find the barn, I searched a map, which, according to its color codes, was mainly tinted light green (indicating cities), but where the barn and yurt stood, it was stark white; the cartographers assumed there was nothing there. I was reminded of Renaissance maps with vast spaces labeled terra incognita,or, playing on my Artaudian vision, hic sunt dracones!

At the barn I found myself among people in their late teens through mid-thirties, all younger than I. The six of us that were new gathered at first on the porch, to be introduced to the practices and integrated into the main body, around 30 people. Some, including my student, Jim, were guides. They would tell us the rules. They spoke quietly and passed the word to one person at a time. We were first told to take off our shoes.

Our small squad was called inside, not by words but by gestures that pointed to where we should sit cross-legged on the floor. Silence. A pair of Haitians entered and sat facing us. Again, silence. One shaman began to croon softly, very slowly. I could not tell at first if there were words to her song. A second voice joined in, also softly. A soft beat from a hand drum, barely audible, gave a pulse; the melody had the sweetness of a lullaby. At some point I thought another voice entered; the melody felt seamless. It grew softer and softer until I realized it was gone. All was silent. After an interval the lullaby started again, softly and sweetly as before.

The languid song tempted me to close my eyes and drift toward sleep. I fought the downward tug; I did not want to miss a thing. I noticed a woman staring at me as she sang. To my left I heard a male voice from one of my group; someone was trying to sing along. I noticed other shamans gesturing and looking at two or three beginners each. We were being invited to sing the song. I recognized foreign words. I could form some of the sounds and made a partial attempt to join the music. I saw eager nods from shamans. Inside of 10 minutes we new folk were singing along, mimicking some of the words and blurring others.

The Haitians stood and moved to the side and behind our seated line. A young man leaned in from behind my right shoulder. He tapped my ear and moved his mouth up close to my face, so I could not miss his lips and tongue as he articulated a phrase. I stored his example, and when the phrase came up again, I sang it loudly—and he nodded and grinned. In this manner, my squad spent the next half hour or so learning the song by rote. I felt elated. I was surprised at how quickly we learned a complex piece of music. We gave no time to discussion; we heard no explanation of the style, and yet we seemed to have absorbed it very well.

The only thing missing was the sense. We hadn’t a clue what we were saying. We discussed this during a break. One of our group, a French speaker, said, “It’s a kind of patois or Creole,” a speech that few outside Hispaniola can understand. “For all we know, we could be cursing our unborn children.” The laughter was brief and tight.

AS WE ERE INTRODUCED TO MORE songs and chants, movement was added. A new shuffling step was very strange. Our postures were strong and vulgar, with nothing lost to gentility. The top half of my body seemed suspended from my waist. A guide showed me how I could sway my shoulders and roll my back in a loose snake-like fashion, while everything from my rump down kept a steady beat. My glutes seemed to rise higher, almost independently, each side competing with my shoulders for height.

The dancing helped us keep the beat, and the beat helped retain the words. We spent hours learning other songs in the rote manner. Everything was gained by imitation; nothing was explained, ever. After absorbing a new song, we would go back over earlier music and discover that we had a lot more to learn. The beat for several of our chants and songs had grown steadily more powerful since our first near-lullaby experience. Now there was a strong insistent erotic beat and an off-beat that inspired extra spurts of energy. As we danced, we would either form into a snake or spin away by ourselves. Either way, the shuffle dance allowed room for improvisation, and that off-beat motivated a lot of cool action.

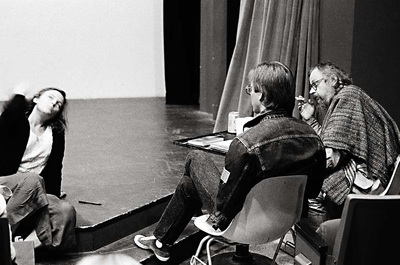

But why were we doing this? What were the words we chanted? I understood that Jerzy did not want to prejudice our reactions by explaining what he was after. But this didn’t stop us from wondering. He would sit in a corner as we went through our paces. A chain smoker, he sat with a coffee can to hold the ashes and butts, and he would watch. A session could run for hours, but he never seemed to tire. He rarely spoke; on occasion he would say a few words to us as a group, or he would invite us out to the porch of the barn, one at a time, to speak privately.

That fall, I arranged to bring the playwright and director Luis Valdez to our campus as a President’s Fellow. In his California-based company Teatro Campesino, Valdez often drew on Chicano roots, and in this he shared Grotowski’s focus on tradition. One evening a faculty group arranged a dinner so Valdez and Grotowski might meet. We gathered at a Mexican restaurant in Santa Ana. Our two guests hit it off from the start. Typically, Jerzy spoke less than Luis, but what they had to share was exuberant and mutually energizing. They sat across from one another, and their heads were close enough that there were times when their conversation dipped into a sort of shared stage whisper. At one point, they chuckled like little boys. I asked what was funny. Valdez replied, “We were laughing at the attitude so many fancy folk adopt. The wealthy…go around in perfume and cologne, like saying, ‘Let’s just forget we were born the same crude way. We come from our mamas’ bellies—from their hard work and labor. We all come raw from blood and sweat and shit!’” Jerzy laughed and nodded vigorously.

Back in the barn in the following days we did not speak of blood, nor of sweat, or shit. When we socialized in breaks from the Work, it was in the yurt—a place exempt from the rule of silence, although we still spoke softly. On occasion people shared food, and sometimes live music was performed, both gifts bringing ethnic touches, a spirit Jerzy furthered by sometimes wearing a Quechua shawl. In the yurt we got to know where people were from.

Occasionally Jerzy gave one of the advanced participants time to perform. I recall an Asian actor beginning a memory exercise as if waking from sleep. He stretched in cat-like movements and mimed morning chores. He hummed a light tune, then mouthed words to the melody. One word he seemed to expel and expectorate in anger. At the end he opened an imaginary door and gazed outward.

Afterward, Jerzy referred to the tune as a lullaby, learned by the actor from his mother, whom he loved and hated—feelings that Jerzy was unable to accept. He took exception to the anger behind the spit-out word, saying it was a “caption, a slogan” meant to “tell us” how the actor felt instead of “bringing your childhood here.”

Instead of indicating anger for his mother, could the actor not have played the contradiction? Shown the mother unloading on him? Might the audience have decided to defend her—or him—depending on the level of insult? Theatre folk are taught to commit to each voice in an agon. The point of view I sought was in the conflict. Grotowski would play each idea, myth, or message for its full worth; challenge the audience to accept or reject what’s before them.

I managed to form an idea, albeit a crude one, of the participation effect Jerzy was seeking, when he spoke to a small group of us one evening. It was dark in the barn; by the light of a lantern, we formed a semicircle. The intimacy was perfect for his talk. He was going on about how certain fantastic “or even miraculous phenomena” may have arisen “in ancient times from hallucinations and willingness to believe, or maybe optical illusions.” He had a book with him, with photographs of Persian carpets. He opened to a particular carpet. “Some say that stories of flying carpets began when men looked at patterns on carpets from special angles, and gained an illusion of flying—of lifting off ….” This was the only time I recall Jerzy speaking to us about the psychophysical effect of art—one that might perhaps bond actors in performance. I could not “see” the angle in that carpet that induced the sensation of flight, but I suspect I might under the right conditions—hypnotic conditions.

BUT NORMALLY, WHEN OUR SUB-group was told anything, it would come to us not from Jerzy, but by word-of-mouth, from someone of the group. This presented a problem, of course, because there was also a natural amount of gossip. Even so, taciturnity was the rule; communications were brief and often whispered. When words are purposely scarce, there is no way to check for authenticity.

We were in effect the lab rats for Jerzy’s research, and for that reason we could not be told what he was looking for or what we were to expect. Some of our exercises seemed totally unrelated to how the chants and dances were affecting us. There was a long night, for instance, when we were just asked to “walk.” How were we to walk? In what “style”? And with or without a destination? These were left unstated. I remember only that I varied my tempo and tried different “character” walks, then tried “inventing” walking. It went on and on. The walk became a marathon, and some people stopped from exhaustion. I determined not to stop. As the oldest walker on the floor, I would not let myself be shamed. More and more pulled themselves off to the side. Still I kept moving, waiting for others to give up. There came a time many minutes later when I was the last person moving. I stopped.

That night, we learned about ourselves. I found out how competitive I was. But what was Jerzy seeing? Was he remembering what he saw? The lack of an explicit agenda has had strange repercussions over the years. Nowadays some lay claim to a certain experience with Jerzy; some tell us what the meaning of it all was. And yet, we each had very private experiences. We worked long hours with high dedication, sharing the same space and the same time, but it cannot be said that we did the Work together.

Still, we all learned one overriding message. Discipline. The one trait that Grotowski actors share is earnest, dedicated striving. There is no arrogance in taking on this superior self-discipline. Our only reward must be found in the fullest commitment to the Work. I had also found or rediscovered a lesson in Jerzy’s principle of blasphemy, of confronting roots. My old wish for a credo seemed answered as Jerzy and his assistants guided performers to a deeply revealing expression that was not pushing an agenda, but exposed our very selves to an audience we trusted to decide who or what we were. We all gave ourselves to the Work with a wonderful modesty.

While we became drained on occasion, we didn’t bow to fatigue. We kept going. We were encouraged by the phenomenon of rote learning. This served as a vivid lesson that our sustained effort would be rewarded; discipline paid! There are essentially two paths to brilliance in our art. The one with which Western performers are familiar is achievement-by-accident. While seeking the Stanislavskian action for our story, we may stumble across inspiration, and add skills as needed. The second path is what we were now experiencing, our ability to apply ourselves in mind-free repetition to acquire the skills needed to perform intricate songs and dances. The skills had to come first, for then we were in a position to unpack them, to interpret and understand them, to trust traditional forms to pave their own way and, as it were, to perform us.

Early on, in one of his rare talks, Jerzy described these paths to us. “Young artists,” he said, “wish for inspired moments. And you find them; you take them; eager artists are bandits. Theatrical moments arrive, and…you grab. Good! You know it will draw attention to you. But you aim to be more than bandits, no? So, okay…now be Samurai.”

Keith Fowler, formerly chief of directing at the Yale School of Drama, is a professor and head of directing emeritus at the University of California-Irvine.

(from http://www.americantheatre.org/ January 8, 2014)

From Inside the Lab

When the Polish theatre guru came to teach in Irvine in the 1980s, he turned the group into a new experiment in mystery and discipline.

BY KEITH FOWLER

In the mid-1960s, grainy pictures and reports reached us from Poland that there were some remarkable dramatic rituals taking place in Wrocław with a group calling itself the Polish Lab Theater. The director was a young man named Jerzy Grotowski, and he identified the style of his work as “poor theatre.”

I was teaching at Williams College, and I was eager to import Grotowski’s visual effects along with whatever I could imagine of his theatrical ideas. I taught a class on Antonin Artaud at the time, and was interested in the “double,” the ineffable presence (like some invisible dragon) that Grotowski’s rites seemed to conjure. I was mounting a production of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine that I ended up directing with what I took to be Grotowski-inspired notions of poor theatre. I was fascinated by the roughness of expression, a crude authenticity that owed nothing to refinement. I admired not only the raw texture, but what I could sense of Grotowski’s point of view. Back then I craved a tangible message—not a dogma, but a credo to guide an audience with intelligence. Troupes that lacked a statement struck me as flabby and weak. Grotowski asserted a vision, but I fear I missed it. I doubt my Tamburlaine had more than a superficial resemblance to the Lab Theater.

Some 15 years later, in 1983, Grotowski joined our department at University of California–Irvine. The details of his arrival included his use of a renovated barn south of our campus. He also required a yurt, a solid-wall version of a Mongolian tent. These structures have become quasi-sacred edifices since his death.

I was pleased that one of my MFA directing students, James Slowiak, was chosen to work with Grotowski’s initial group. A bright and curious artist, Jim swiftly earned Jerzy’s trust, becoming his personal assistant for many years. As for the faculty, after an initial meeting, we had no regular contact with “Groto,” the students’ affectionate name for him. As the academic year got under way, I felt left out. I told our chair I wanted to join in. Weeks later, I received a nighttime phone call; an unknown male voice told me to come to an address in Laguna Beach the next evening. “Wait,” I said, as he was about to hang up, “What is this address?”

“It’s where Jerzy is staying.” Click.

Laguna Beach is a touristy seaside city, an artists’ colony and beach volleyball Mecca of fewer than 25,000 people, 20 miles south of Irvine. It was not where I had pictured Grotowski.

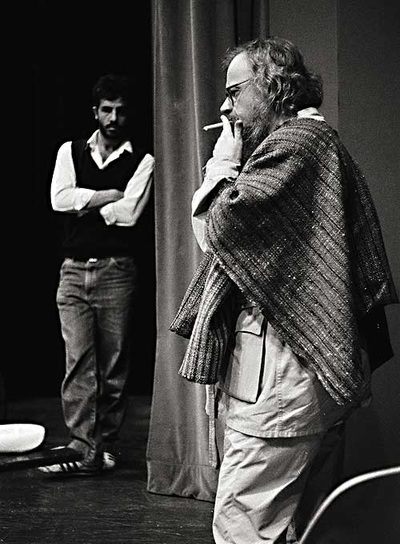

The next night I arrived at the address and rang the bell. Jerzy appeared, with a cigarette in his hand, wearing a dark sweater with a darker sport coat over it, his shoulder-length hair damp and uncombed. He said softly, “We go to the café, yes?” He nodded vigorously toward the corner and started in that direction. He led us silently toward the White House, a popular tavern. He aimed for the back—to a section quieter than the traffic in front.

I asked the waiter for a beer. Jerzy ordered a meal, and we began to talk. I learned that the Work, “Objective Drama,” involved exposing performers to Haitian shamanic traditions. Students would be instructed in song and dance by practi-tioners of Afro-Haitian-Catholic hybrids of Santeria andVodou. And, as I would learn in our group’s dryly joking fashion, our masters were witch doctors. The aim seemed to be to discover what, if any, effect such age-old rituals might have on us. Whether thisparticipation effect might be a revival of old skills or an impact on our ideas of self, I never knew.

THERE WAS MUCH I NEVER KNEW. Years later, hearing from others what Jerzy was doing, I realized how his legacy could be, in Richard Schechner’s words, so “well known and obscure simultaneously.” Lisa Wolford’s research pinpoints his elusiveness and changeability. Given that he shared little information directly with his subjects, we confabulated explanations for his protocols and exercises. It is fair to say that all who worked with him had a unique experience.

The White House jukebox played “Hotel California.” As Jerzy came to the end of his meal, I asked how he was enjoying California. He nodded quickly. “I like it here,” he said, “with young people who are so beautiful, healthy and smart.” The waiter brought the bill. I reached for my wallet, but Jerzy was already prepared. “Please,” he said, and handed his credit card to the waiter. Whenever I think back on that evening, I smile to think of Jerzy Grotowski treating me in a California saloon with his American Express Gold.

He never said that I was admitted to the group, but I was later informed of the starting date. To find the barn, I searched a map, which, according to its color codes, was mainly tinted light green (indicating cities), but where the barn and yurt stood, it was stark white; the cartographers assumed there was nothing there. I was reminded of Renaissance maps with vast spaces labeled terra incognita,or, playing on my Artaudian vision, hic sunt dracones!

At the barn I found myself among people in their late teens through mid-thirties, all younger than I. The six of us that were new gathered at first on the porch, to be introduced to the practices and integrated into the main body, around 30 people. Some, including my student, Jim, were guides. They would tell us the rules. They spoke quietly and passed the word to one person at a time. We were first told to take off our shoes.

Our small squad was called inside, not by words but by gestures that pointed to where we should sit cross-legged on the floor. Silence. A pair of Haitians entered and sat facing us. Again, silence. One shaman began to croon softly, very slowly. I could not tell at first if there were words to her song. A second voice joined in, also softly. A soft beat from a hand drum, barely audible, gave a pulse; the melody had the sweetness of a lullaby. At some point I thought another voice entered; the melody felt seamless. It grew softer and softer until I realized it was gone. All was silent. After an interval the lullaby started again, softly and sweetly as before.

The languid song tempted me to close my eyes and drift toward sleep. I fought the downward tug; I did not want to miss a thing. I noticed a woman staring at me as she sang. To my left I heard a male voice from one of my group; someone was trying to sing along. I noticed other shamans gesturing and looking at two or three beginners each. We were being invited to sing the song. I recognized foreign words. I could form some of the sounds and made a partial attempt to join the music. I saw eager nods from shamans. Inside of 10 minutes we new folk were singing along, mimicking some of the words and blurring others.

The Haitians stood and moved to the side and behind our seated line. A young man leaned in from behind my right shoulder. He tapped my ear and moved his mouth up close to my face, so I could not miss his lips and tongue as he articulated a phrase. I stored his example, and when the phrase came up again, I sang it loudly—and he nodded and grinned. In this manner, my squad spent the next half hour or so learning the song by rote. I felt elated. I was surprised at how quickly we learned a complex piece of music. We gave no time to discussion; we heard no explanation of the style, and yet we seemed to have absorbed it very well.

The only thing missing was the sense. We hadn’t a clue what we were saying. We discussed this during a break. One of our group, a French speaker, said, “It’s a kind of patois or Creole,” a speech that few outside Hispaniola can understand. “For all we know, we could be cursing our unborn children.” The laughter was brief and tight.

AS WE ERE INTRODUCED TO MORE songs and chants, movement was added. A new shuffling step was very strange. Our postures were strong and vulgar, with nothing lost to gentility. The top half of my body seemed suspended from my waist. A guide showed me how I could sway my shoulders and roll my back in a loose snake-like fashion, while everything from my rump down kept a steady beat. My glutes seemed to rise higher, almost independently, each side competing with my shoulders for height.

The dancing helped us keep the beat, and the beat helped retain the words. We spent hours learning other songs in the rote manner. Everything was gained by imitation; nothing was explained, ever. After absorbing a new song, we would go back over earlier music and discover that we had a lot more to learn. The beat for several of our chants and songs had grown steadily more powerful since our first near-lullaby experience. Now there was a strong insistent erotic beat and an off-beat that inspired extra spurts of energy. As we danced, we would either form into a snake or spin away by ourselves. Either way, the shuffle dance allowed room for improvisation, and that off-beat motivated a lot of cool action.

But why were we doing this? What were the words we chanted? I understood that Jerzy did not want to prejudice our reactions by explaining what he was after. But this didn’t stop us from wondering. He would sit in a corner as we went through our paces. A chain smoker, he sat with a coffee can to hold the ashes and butts, and he would watch. A session could run for hours, but he never seemed to tire. He rarely spoke; on occasion he would say a few words to us as a group, or he would invite us out to the porch of the barn, one at a time, to speak privately.

That fall, I arranged to bring the playwright and director Luis Valdez to our campus as a President’s Fellow. In his California-based company Teatro Campesino, Valdez often drew on Chicano roots, and in this he shared Grotowski’s focus on tradition. One evening a faculty group arranged a dinner so Valdez and Grotowski might meet. We gathered at a Mexican restaurant in Santa Ana. Our two guests hit it off from the start. Typically, Jerzy spoke less than Luis, but what they had to share was exuberant and mutually energizing. They sat across from one another, and their heads were close enough that there were times when their conversation dipped into a sort of shared stage whisper. At one point, they chuckled like little boys. I asked what was funny. Valdez replied, “We were laughing at the attitude so many fancy folk adopt. The wealthy…go around in perfume and cologne, like saying, ‘Let’s just forget we were born the same crude way. We come from our mamas’ bellies—from their hard work and labor. We all come raw from blood and sweat and shit!’” Jerzy laughed and nodded vigorously.

Back in the barn in the following days we did not speak of blood, nor of sweat, or shit. When we socialized in breaks from the Work, it was in the yurt—a place exempt from the rule of silence, although we still spoke softly. On occasion people shared food, and sometimes live music was performed, both gifts bringing ethnic touches, a spirit Jerzy furthered by sometimes wearing a Quechua shawl. In the yurt we got to know where people were from.

Occasionally Jerzy gave one of the advanced participants time to perform. I recall an Asian actor beginning a memory exercise as if waking from sleep. He stretched in cat-like movements and mimed morning chores. He hummed a light tune, then mouthed words to the melody. One word he seemed to expel and expectorate in anger. At the end he opened an imaginary door and gazed outward.

Afterward, Jerzy referred to the tune as a lullaby, learned by the actor from his mother, whom he loved and hated—feelings that Jerzy was unable to accept. He took exception to the anger behind the spit-out word, saying it was a “caption, a slogan” meant to “tell us” how the actor felt instead of “bringing your childhood here.”

Instead of indicating anger for his mother, could the actor not have played the contradiction? Shown the mother unloading on him? Might the audience have decided to defend her—or him—depending on the level of insult? Theatre folk are taught to commit to each voice in an agon. The point of view I sought was in the conflict. Grotowski would play each idea, myth, or message for its full worth; challenge the audience to accept or reject what’s before them.

I managed to form an idea, albeit a crude one, of the participation effect Jerzy was seeking, when he spoke to a small group of us one evening. It was dark in the barn; by the light of a lantern, we formed a semicircle. The intimacy was perfect for his talk. He was going on about how certain fantastic “or even miraculous phenomena” may have arisen “in ancient times from hallucinations and willingness to believe, or maybe optical illusions.” He had a book with him, with photographs of Persian carpets. He opened to a particular carpet. “Some say that stories of flying carpets began when men looked at patterns on carpets from special angles, and gained an illusion of flying—of lifting off ….” This was the only time I recall Jerzy speaking to us about the psychophysical effect of art—one that might perhaps bond actors in performance. I could not “see” the angle in that carpet that induced the sensation of flight, but I suspect I might under the right conditions—hypnotic conditions.

BUT NORMALLY, WHEN OUR SUB-group was told anything, it would come to us not from Jerzy, but by word-of-mouth, from someone of the group. This presented a problem, of course, because there was also a natural amount of gossip. Even so, taciturnity was the rule; communications were brief and often whispered. When words are purposely scarce, there is no way to check for authenticity.

We were in effect the lab rats for Jerzy’s research, and for that reason we could not be told what he was looking for or what we were to expect. Some of our exercises seemed totally unrelated to how the chants and dances were affecting us. There was a long night, for instance, when we were just asked to “walk.” How were we to walk? In what “style”? And with or without a destination? These were left unstated. I remember only that I varied my tempo and tried different “character” walks, then tried “inventing” walking. It went on and on. The walk became a marathon, and some people stopped from exhaustion. I determined not to stop. As the oldest walker on the floor, I would not let myself be shamed. More and more pulled themselves off to the side. Still I kept moving, waiting for others to give up. There came a time many minutes later when I was the last person moving. I stopped.

That night, we learned about ourselves. I found out how competitive I was. But what was Jerzy seeing? Was he remembering what he saw? The lack of an explicit agenda has had strange repercussions over the years. Nowadays some lay claim to a certain experience with Jerzy; some tell us what the meaning of it all was. And yet, we each had very private experiences. We worked long hours with high dedication, sharing the same space and the same time, but it cannot be said that we did the Work together.

Still, we all learned one overriding message. Discipline. The one trait that Grotowski actors share is earnest, dedicated striving. There is no arrogance in taking on this superior self-discipline. Our only reward must be found in the fullest commitment to the Work. I had also found or rediscovered a lesson in Jerzy’s principle of blasphemy, of confronting roots. My old wish for a credo seemed answered as Jerzy and his assistants guided performers to a deeply revealing expression that was not pushing an agenda, but exposed our very selves to an audience we trusted to decide who or what we were. We all gave ourselves to the Work with a wonderful modesty.

While we became drained on occasion, we didn’t bow to fatigue. We kept going. We were encouraged by the phenomenon of rote learning. This served as a vivid lesson that our sustained effort would be rewarded; discipline paid! There are essentially two paths to brilliance in our art. The one with which Western performers are familiar is achievement-by-accident. While seeking the Stanislavskian action for our story, we may stumble across inspiration, and add skills as needed. The second path is what we were now experiencing, our ability to apply ourselves in mind-free repetition to acquire the skills needed to perform intricate songs and dances. The skills had to come first, for then we were in a position to unpack them, to interpret and understand them, to trust traditional forms to pave their own way and, as it were, to perform us.

Early on, in one of his rare talks, Jerzy described these paths to us. “Young artists,” he said, “wish for inspired moments. And you find them; you take them; eager artists are bandits. Theatrical moments arrive, and…you grab. Good! You know it will draw attention to you. But you aim to be more than bandits, no? So, okay…now be Samurai.”

Keith Fowler, formerly chief of directing at the Yale School of Drama, is a professor and head of directing emeritus at the University of California-Irvine.

(from http://www.americantheatre.org/ January 8, 2014)